ITEMS PRESENTED AND DISCUSSED AT THE NOVEMBER MEETING

Sections PS 1000 and PS 3210: Can a public sector entity recognize an asset for carbon credits?

The submission asked the Group to consider how carbon credits may meet definition of an asset as provided for in Section PS 1000,1 Financial Statement Concepts, and Section PS 3210, Assets.

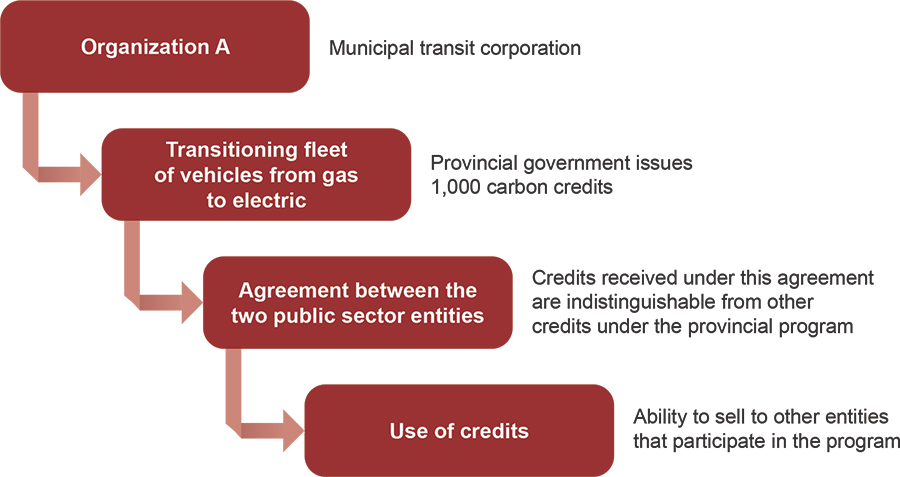

The submission presented the following scenario and asked the Group whether definition of an asset is met and, if so, whether disclosure is required under the standards:

- Organization A has no compliance obligations. So, it has no need to use the credits and it intends to sell them on the market within three months of receipt.

- Carbon credits can be traded in the provincially regulated markets through brokers to other participants in the program. The provincial government must approve transactions in the credits.

- The provincial government does not recognize a financial liability for carbon credits in the consolidated provincial accounts.

- Organization A has publicly stated it intends to sell any carbon credits obtained and to reinvest proceeds in green initiatives in the municipality.

- Organization A’s Internal policy sets out how and when the credits will be exchanged in the market.

- Transactions to sell the credits are assumed to be material.

Issue 1 – Do carbon credits meet the definition of an asset under Sections PS 1000 and PS 3210?

The Group was asked to consider whether carbon credits meet the definition of an asset (View A) or not (View B).

Most Group members supported View A, indicating that the asset definition is met because:

- Control over the carbon credits exists. This assumes the province would approve transactions in the credits. If approval was unlikely, then the province would not issue them and the market for such credits would be undermined. Past practice indicates that the province is unlikely to intervene in a transaction.

- Further, control exists since the organization can decide:

- to sell the carbon credits;

- to hold the carbon credits; and

- to whom they wish to sell the credits.

- The province’s involvement is an administrative exercise and Organization A maintains control.

- The ability to sell the carbon credits is established. Selling the credits in an active market will result in future economic benefits.

- Organization A’s transitioning its vehicle fleet from gas to electric earned it the credits and this comprises the past event that created the asset.

A few Group members noted that View B had merit because of uncertainties relating to provincial approval and thus Organization A’s control of the future economic benefits associated with the credits:

- The province may deny future transactions to sell the credits. Although the province has not done so in the past, circumstances may change, and the province could deny or re-assess transactions. Provincial changes in policies frequently occur. Ministerial discretion to approve or not is likely retained regardless of past practice.

- The key provincial objective of issuing carbon credits is to support green initiatives. Some Group members felt the province’s agreement on such transactions may be contingent on the proceeds of sale being used for green initiatives. Without such restrictions, there is a risk that the credits would be just another funding source, a form of government transfer. And if the sale proceeds are not used for green initiatives, there is some potential for provincial claw back.

- A change in provincial government could also affect the market for and issuance of carbon credits. At a minimum, an entity should assess the likelihood of provincial approval on a regular basis, similar to the assessment done for allowances for doubtful accounts.

Issue 2 – What kind of asset are the carbon credits under public sector accounting standards (PSAS)?

For discussing Issue 2, the Group assumed the credits meet the definition of an asset for Organization A.

If the carbon credits meet the definition of an asset, Organization A needs to consider what kind of asset the carbon credits represent before determining what recognition and measurement guidance applies to those assets.

Carbon credits are part of a market that allows polluters either to pay for credits or to invest in reducing carbon emissions. At some point, it will become uneconomical for polluters to buy credits rather than invest, especially if the province increases the costs of carbon credits or increases the requirements around carbon emissions. These factors could affect an organization’s ability to sell carbon credits.

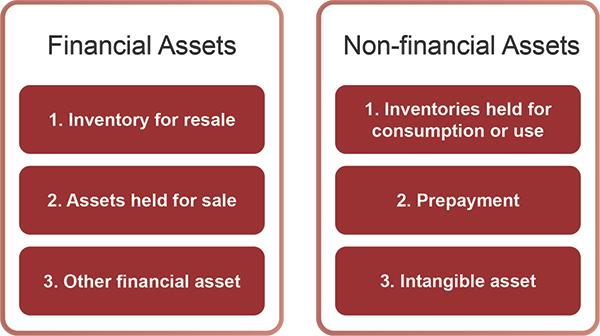

The following types of assets were identified for Group members to consider:

In considering the nature of the asset, some Group members referred to the definition of an intangible asset in Purchased Intangibles, paragraphs PSG-8.6-7, and to the definition of a financial asset in paragraph PS 1000.40. Group members were also asked to consider if their answer would change if Organization A’s intent was to use the credits rather than sell them.

Specifically, if Organization A held the credits for its own use rather than for sale (i.e., to offset against an emissions obligation that Organization A has incurred), would the credits still be a financial asset? Assume that the mechanism for cash conversion exists (a marketplace) even if it is not the entity’s intent to convert the credits into cash, but to monetize them by using them to reduce a liability.

Ultimately, most Group members indicated some support for classifying the carbon credits as an “other” type of financial asset, but also acknowledged that the intent of the entity holding the credits would affect asset classification. Classification as inventory was somewhat problematic, as in most cases the credits would not form part of an entity’s core operations. If designated as an “other” type of asset held for sale, the burden of proof that the credits are truly designated for sale required by Section PS 1201, Financial Statement Presentation, would come into play. And, only purchased intangibles can be recognized in financial statements. There is some question whether the credits issued by the province to Organization A can be considered “purchased.” The classification of such credits has implications for the net debt indicator, too, depending on whether they are classified as financial assets or non-financial assets. So, the classification of such credits and whether they should form part of the net debt calculation are also considerations.

In reaching these conclusions, Group members shared the following points:

- If the credits are to be resold, they are more likely to meet the definition of a financial asset,2 than the definition of an intangible asset. However, some Group members noted that if there is no intent to resell the credits, they may better meet the definition of an intangible asset.3

- Carbon credits should be classified as inventory for resale or another asset for sale as allowed in Section PS 1201, if there is an intent to sell. Intent is relevant to determining classification:

- If the organization intends to sell and convert the credits to cash, then the intent as to timing of sale may be relevant. If the intent is to sell within one year and the requirements of Section PS 1201 are met, then it may be a (financial) asset for sale. If intent is to hold the credits for longer than a year and possibly sell later, then some kind of “other financial asset” classification may be appropriate.

- If the intent is to use the credits, they are not really an inventory for use in the same way as gravel, parts, or other supplies. They lack the physical substance traditionally associated with inventory. The entity cannot readily replenish the “stock” of carbon credits. And the Organization A’s core business or operations is not to hold and trade such credits.

- Credits would be a short-term investment recognized as an asset on the assumption that there is an open market for the credits and that the province does not limit who purchasers can be.

- It is important to assess and interpret each situation, including:

- the intended use of the credits;

- any contractual obligations and definitions affecting use of the credits, including provincial restrictions or regulations; and

- whether the credits constitute a prepayment if the entity intends to use them itself, or not a prepayment, if the entity intends to sell them and there is an ability to resell the credits.

Many Group members noted that fact patterns are likely to determine the type of asset. Individual carbon-credit arrangements would need to be reviewed in determining an appropriate approach. For example:

- One Group member noted the similarity to fishing licenses, which are recognized as intangible assets as they are held for the use by the organization, similar to carbon credits. While carbon credits lack physical substance, if the intent is to sell them, they are better classified as a financial asset.

- If the credits are held for the entity’s own use rather than for sale, they remain a realizable asset that is convertible into cash and should be classified as a financial asset. If the entity retains a contractual right to sell the credits in the future, could the credits give rise to a new type of financial instrument?

- One Group member noted that paragraph 2 of PSG-8 would scope out the credits being classified as an intangible asset because they are in the nature of a contribution or transfer from the province.4 Other Group members felt the carbon credits are intangible in nature. One questioned whether intangibles held for sale could be classified as a financial asset.

Issue 3 – What recognition standards apply to the carbon credits?

The Group was asked to consider three views:

- View A: Carbon credits are an intangible asset that is not recognized under PSAS.

- View B: Carbon credits are a financial asset and therefore can be recognized under PSAS, regardless of their intangible nature.

- View C: Carbon credits are an intangible asset that can be recognized under PSAS.

The Group agreed the answers to Issues, 1, 2, and 3 should be consistent, and View B would most closely achieve this objective. Nevertheless, Organization A’s intent for the carbon credits remained a factor.

The Group was asked to consider paragraph PS 1000.58 qualifying the prohibition of intangibles by allowing only recognition of purchased intangibles.5 Developed or “non-purchased” intangibles specifically cannot be recognized. “Granted” or “earned” intangibles are not mentioned, but these could fit under “non-purchased”.

The Group concluded that the carbon credits, as defined in the submission’s fact patterns, would not meet the definition of a purchased intangible asset. So, View A was not possible under existing generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), though it held appeal for some Group members. They raised a concern that View A might make the credits invisible assets to users and thus be misleading. If View A were adopted, some Group members indicated that disclosure would be necessary to partially mitigate this concern. One Group member expressed the view that recognition prohibitions prevent public sector entities from dealing with new items. The Group encouraged PSAB to consider intangibles more broadly and carbon credits specifically should it initiate a project on intangibles.

Some Group members raised the liability question, noting that if an organization does not meet government-imposed emission targets or other metrics, there may be a liability to be recognized.

Issue 4 asked about the impact of receiving carbon credits from a related party. The Group thought it overlapped with the points discussed for the other three issues and deferred it for possible future consideration as practice develops on accounting for carbon credits.

1 Material that links to the CPA Canada Handbook is available to subscribers only. However, all information needed to respond is provided in this meeting report.

2 Paragraph PS 1000.39 defines financial assets as “assets that could be used to discharge existing liabilities or finance future operations and are not for consumption in the normal course of operations.”

3 PSG-8, paragraph 1, defines purchased intangibles as: “identifiable non-monetary economic resources without physical substance acquired through an arm's length exchange transaction between knowledgeable, willing parties who are under no compulsion to act.” Only purchased intangibles can be recognized in financial statements per the paragraph PS 1000.57.

4 Paragraph 2 of PSG-8: Intangibles acquired through a transfer, contribution or inter-entity transaction, are not purchased intangibles.

5 Paragraph PS 1000.58: “In the absence of appropriate public sector recognition and measurement criteria for intangibles, all intangibles, including those that have been purchased developed construction or inherited in right of the crown, are not recognized as asset in government financial statements.” [italics added for emphasis].

Back to top

Presenting certain items on the statement of cash flows

The submission was positioned as an application of existing standards in preparing general-purpose financial statements for a public sector entity applying the PSA Handbook as its primary source of GAAP. The submission raised two issues regarding how public sector entities should present the cash flows relating to public private partnerships and the asset retirement obligations in the statement of cash flows. A third issue asked whether restricted cash should be included in cash and cash equivalents; in cash flows from investing activities; or in cash flows from operating, investing, capital, or financing activities, as appropriate to the nature of the restrictions.

The issues stem from:

- Existing reporting model standard Section PS 1201 (and the Exposure Draft, “Financial Statement Presentation, Proposed Section PS 1202”) do not specify how certain transactions are to be presented in the cash flow statement.

- Existing Section PS 1201 and proposed new Section PS 1202 do not go into the detail necessary to address the presentation questions raised because they are not focused solely on the cash flow statement.

- International Accounting Standard (IAS) 7 Statement of Cash Flows and International Public Sector Accounting Standard (IPSAS) 2, Cash Flow Statements, have separate standards and include more detailed guidance on the cash flow statement, providing presentation requirements for many specific items.

Issue 1 – How should public sector entities reflect cash flows related to public private partnership arrangements (3Ps) in the statement of cash flows, in cash flows from capital activities, or cash flows from financing activities?

The issue asked the Group to consider whether cash flows related to operations or maintenance for infrastructure assets should be presented in cash flows from capital activities (View A) or from financing activities (View B).

A Group member clarified that the starting point for 3Ps is not acquiring infrastructure or securing alternate financing for capital but managing risk. So, accounting disclosures must help in evaluating if the 3P was successful: Was it effective? Did it transfer risk, etc.? This would include breaking out the cash flows into capital, financing, operating, and maintenance as appropriate. Another Group member countered that smaller governments may use 3Ps as a financing tool.

The Group discussed the various components that can be introduced on 3Ps. A Group member outlined the several possible components of a 3P arrangement, such as design, build, finance, operate, and maintain (DBFOM). Some Group members noted that the benefit derived from 3Ps, such as from DBFOM arrangements, have become more common. They shared that such arrangements in procuring public infrastructure are beneficial in sharing the risks in terms of financing and construction, from design and planning to long-term maintenance, for example. Two Group members thought there was some appeal to splitting cash flows into such components, but acknowledged the additional complexity and decreased understandability for users.

Most Group members supported View B. They indicated that 3P cash flows should be presented as financing activities because the main motivation for a 3P arrangement is to access an alternative financing model for infrastructure. They noted the following:

- In many instances, governments cannot afford to purchase or replace their infrastructure. Certain projects require significant investments that public sector entities cannot self-finance. Governments often use 3Ps to help finance such projects and so this would represent a financing activity.

- Section PS 1201 links financing activities with the cash repayment of debt. Many 3P arrangements explicitly provide for repayment, which would support designating 3P cash flows being from financing activities.

- If the 3P project’s ultimate intent is to offer a public service, then this would represent an activity to finance the delivery costs of a public service.

- The transfer of risks in the development of infrastructure assets may be transferred from the public sector to the private sector partner. A Group member noted that Section PS 3160, Public Private Partnerships, clearly addresses discount rates and estimating the liability, which seems most relevant to a financing activity.

- Section PS 3160 establishes that a public entity recognizes a liability when it recognizes an infrastructure asset. In addition, the type of consideration provided to the private sector partner determines whether the public sector entity recognizes a financial liability (financial liability model) or a performance obligation (user-pay model).6

The details and components of 3P agreements must be considered in determining whether the cash flows derived from the infrastructure asset should be presented as financing or capital activities. One Group member noted the existence of balloon payments in some arrangements, which may imply more of a capital activity (i.e., acquisition of infrastructure). Other arrangements involve service payments over several years, which may more closely resemble a financing activity. Another member agreed, indicating the substance of an arrangement may make a third view more appropriate (i.e., splitting the cash flows related to the 3P according to their objective and substance). Cost-benefit of splitting would be a consideration, as would the degree of transparency provided to readers.

Issue 2 – How should public sector entities present cash flows related to asset retirement obligations (AROs) in the statement of cash flows?

The Group was asked to consider whether cash flows related to AROs should be presented in cash flows from capital activities (View A) or from operating activities (View B).

Most Group members supported View A:

- An ARO would form part of the cost of capital items and should be presented as part of capital activities.

- In circumstances where the asset may still be in productive use, the cash flows would be capital activities in nature and should be presented as such.

- While Section PS 1201 is generic, it better suits the cash flows related to AROs as a capital activity.

- Constitutes as a capital activity because AROs only arise because an entity has a tangible capital asset. They are not driven by activities from ongoing operations.

Some Group members noted circumstances where View B may have merit or suggested other considerations:

- If an asset is fully depreciated, cash flows may be better reflected as cash derived from operating activities.

The nature of the business/activity of the entity holding the asset might be relevant to the classification of the ARO cash flows. For example, the cash flows of AROs related to defence assets might be classified differently if the assets are used on the battlefield (i.e., in operations), versus used in training (i.e., capital activities). Splitting the cash flows from the ARO may have merit. At inception, the ARO cash flows are considered related to capital activities. However, the interest accretion over time is reflected in the operating statement and thus in cash flow from operating activities over time.

Issue 3 – Should restricted cash be included in cash and cash equivalents on the statement of cash flow?

The Group was asked to consider three views:

- View A: Restricted cash should be included in cash and cash equivalents on the statement of cash flow.

- View B: Changes in restricted cash in the accounting period should be presented in cash flows from investing activities.

- View C: Changes in restricted cash in the accounting period should be presented in cash flows from operating, investing, capital, or financing activities, as appropriate to the nature of the restrictions.

Most Group members supported View C, that restricted cash would not be included in the cash and cash equivalents balance reconciled in the statement of cash flows.

However, many Group members offered thoughts on where View A or B may also apply. Comments included:

- Restricted cash should be identified separately on the statement of financial position, as this would be useful to users of financial statements. However, Section PS 3100, Restricted Assets and Revenues, does not allow restricted amounts to be presented separately.

- Disclosure of the restrictions and what the cash must be used for in the notes and schedules would be good accountability information.

- Separately reporting cash flows related to restricted cash in the categories of cash flow activities that best reflect the restrictions would provide good cash flow information for users.

- The presentation of the details of the restrictions may be a matter of public interest that should be disclosed and presented appropriately on statement of cash flow;

- One Group member noted support for View A, referring to the IFRS Interpretations Committee’s April 2022, APA12A: Finalisation of agenda decision. This decision concluded that restricted cash is still considered to be cash, even if the entity does not have the intention for use in the short term.

- Another Group member reflected that Section PS 1201 does not clearly define cash and noted it is logical to include all items that by their nature comprise cash, even if their use is restricted. Cash is cash. Restricted cash should be reported as part of the cash and cash equivalents balance that is reconciled to on the statement of cash flow.

- A Group member felt that cash flows related to restricted cash should be reflected in investing activities as changes in cash are investing activities.

- Still another Group member questioned if the complexity associated with View C is justifiable or if the user might better understand that all cash, including restricted cash, was included in the cash and cash equivalents balances reconciled to in the statement of cash flows.

The Group encouraged PSAB to provide further guidance on the presentation of items in the statement of cash flows, including restricted cash.

6 Section PS 3160 provides several recognition and disclosure considerations. However, the standard does not explicitly clarify how cash flows related to the infrastructure asset should be presented in the statement of cash flows.

Back to top

Cloud computing: The impact of recent PSA Handbook changes on accounting for implementation costs

The submission asked the Group to consider whether implementation costs related to cloud computing arrangements that are service arrangements should be capitalized or expensed under PSAS in light of the recent guidance issued by PSAB and other standard setters. For example:

- PSAB issued PSG-8, which opens the door to recognizing purchased intangibles in public sector financial statements.

- The IFRS Interpretations Committee (IFRIC) the released an agenda decision (March 2021) on accounting treatment of costs of configuring or customizing a supplier’s application software in a cloud computing arrangement that is a service arrangement.7

- PSAB’s International Strategy is now in effect. The implementation of this strategy included the amending of Section PS 1150, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, to position IPSAS as the first accounting framework for public sector entities to consult in situations not covered by primary sources of GAAP or for assistance in applying primary sources of GAAP to specific circumstances, when a public sector entity chooses to look outside the PSA Handbook for additional guidance.

- The Financial Accounting Standards Board issued ASU 2018-15 (Customer’s accounting for implementation costs incurred in a cloud computing arrangement that is a service) effectively aligning the accounting for implementation costs for hosting arrangements, regardless of whether they convey a license to the software or represent a service arrangement.

- The Canadian Accounting Standards Board (AcSB) issued the Exposure Draft in March 2022 proposing the issuance of Accounting Guideline (AcG) 20, Customer’s Accounting for Cloud Computing Arrangements.8 The Guideline would apply to private sector entities following accounting standards for private enterprises (ASPE) and private sector not-for-profit organizations following accounting standards for not-for-profit organizations.

Cloud computing arrangements are becoming more prevalent in the public sector and involve significant investment. As noted during previous Group meetings (October 2015 and July 2020) PSAS do not directly address the questions of:

- accounting for payments made to a cloud computing provider for the underlying cloud computing arrangement; or

- accounting for related implementation costs.

Issue 1 – Considering the recent changes to accounting frameworks, how should a customer account for implementation costs incurred in a cloud computing arrangement that is a service under PSAS?

The Group was asked to consider whether all implementation costs should be capitalized (View A) or expensed (View B).

Most Group members supported View B, and shared the following:

- The underlying cloud computing software would be controlled by the supplier, not by the customer (so it is not an asset of the customer). Implementation costs on their own do not provide future economic benefits; these only arise in conjunction with the software. As the software is controlled by the supplier, implementation costs cannot be capitalized on their own by the customer.

- There is no prevailing view from other standard setters as to the most appropriate accounting for these circumstances.

- Some Group members distinguished having the software on-premises versus in the cloud and what the implications of this distinction were for accounting purposes. They noted that while an on-premises system may be capitalized, it would be helpful for PSAB to provide further guidance on cloud computing arrangements. A Group member noted that the same level of service is provided to public sector entities for a cloud-based service, as it is for an on-premises application. The Group reflected on the following while discussing the implications of an on-premises software versus a cloud-based one:

- Extensive upfront costs

- Similar implementation costs

- Platforms and solutions have evolved more toward cloud-based ones (on-premises solutions are becoming outdated)

- Replacement of software assets and service-level contracts are becoming more complex

- Technological advancements have outpaced the development of accounting standards

- Another Group member stated while it can be argued such costs should be capitalized, current PSAS guidance explicitly prohibits accounting for developed or inherited intangibles as assets and so implementation costs for cloud computing arrangements need to be expensed.

- A practical and preferred approach would be to capitalize and amortize implementation costs related to cloud computing arrangements that are a service. However, public sector entities must adhere to current standards. The implicit approach given the current PSAS guidance is to expense such costs as they are incurred.

A few Group members raised concern with having to expense cloud computing arrangement as this may result in skewing the financial position of many public sector entities. Also, some Group members thought that the implementation costs have a value on their own. They gave examples where municipalities incur significant costs involving cloud computing arrangements. Expensing such costs, rather than capitalizing and amortizing them over the period of the contract, poses a challenge to how to reflect such costs in financial statements and to explain them to council and to citizens.

One Group member supported View A, providing an example where a software provider would no longer support the on-premises software system. A significant investment was required to upgrade the system to a cloud-based one. In this instance, it was determined to capitalize the cloud-based enterprise finance system and amortize such costs over the period of the contract.

The Group discussed if conclusions on the views provided in the submission would depend on the nature of the implementation activities. Many Group members reflected that the concept of control would still be relevant as the cloud-based software is controlled by the supplier. So, if the customer does not control the future economic benefits without proprietary access to the software, there would still be the need to expense the implementation costs related to the cloud computing arrangement, unless some of those implementation costs met the definition of an asset in their own right.

One Group member noted that exceptions should be explored, referencing the AcSB’s Exposure Draft for AcG-20,9 which will form part of ASPE. Added similar flexibility and clarity on how to account for cloud computing arrangements and related implementation costs under PSAS would be welcomed would be welcomed.

The Group reflected on the recent decisions from other standard setters and noted that cloud computing has been discussed at prior Group meetings. The Group encouraged PSAB to address the concerns discussed by providing further clarity and guidance regarding intangibles in general and specifically cloud computing arrangements, as well as related implementation costs.

7 IASB, “IFRIC Update March 2021. ”See “Configuration or Customisation Costs in a Cloud Computing Arrangement (IAS 31 Intangible Assets) – Agenda Paper 2”, published in April 2021, for full details of the agenda decision.

8 AcG-20 was issued to Part II of the CPA Canada Handbook and released on November 15, 2022.

9 The Exposure Draft explored:

- how existing Sections in ASPE should be applied when accounting for cloud computing arrangements;

- a simplified approach to ease the accounting requirements for such arrangements; and

- concerns that the accounting outcome for expenditures on implementation activities in a certain situation does not reflect the economic benefits an enterprise receives over time.

Back to top

Cloud computing: Accounting for implementation costs in the context of a government partnership

The submission referred to the same background as the previous topic but asked the Group to consider how individual partners should account under PSAS for the implementation costs they incur as a result of a cloud computing arrangement that is a service in the context of a government partnership

The submission presented the following scenario for the Group to consider as part of the discussion:

- A contractual arrangement was entered into by 10 hospitals that follow PSAS (without the use of the PS 4200 Series).

- In accordance with the terms of the contractual arrangement, a separate entity has been incorporated that will follow PSAS.

- The contractual arrangement was entered into, and the new entity was formed to design and develop computing software. The new entity will provide each hospital access to the software through the cloud in a long-term licensing arrangement that is part of the original contractual arrangement.

- Each hospital made an initial financial investment in the entity and took back a one-tenth “interest” in the new entity. This financial investment was used to finance the development of the cloud computing software.

- The new entity is run by a board of 10 directors. Each hospital appoints one director who services for a three-year term. The board operates in accordance with the terms of the contractual arrangement and holds meetings on a regular basis. All key decisions must be made by unanimous consent and all other decisions are made by majority vote.

- Each hospital will share the costs associated with continual software maintenance and upgrades through an annual subscription fee and will share on an equitable basis the significant risks and benefits associated the operations of the new entity.

- The new entity has engaged a third-party software developer to develop and upgrade the bespoke software on the new entity’s behalf. The new entity owns the intellectual property and has exclusive rights to the software, including when and how to update or reconfigure the software.

- Each hospital incurs significant implementation costs to access and use the software. These implementation costs include costs to:

- customize or configure the cloud-based software;

- develop and implement interfaces between the hospital’s existing systems and the cloud-based software; and

- convert/migrate existing data for use by the cloud-based software.

- The new entity will not provide access to the software to any entities other than the partners to the contractual arrangement.

Additional it is determined that:

- The new entity meets the definition of a non-business government partnership. In accordance with PSAS, each individual partner will proportionately consolidate its one-tenth interest in the government partnership.

- The cloud computing software is an asset of the government partnership and the government partnership accounts for it as computing software in accordance with Section PS 3150, Tangible Capital Assets.

- For each individual partner, the arrangement is a cloud computing arrangement that is a service.

The issue asked the Group to consider two views related to the fact pattern:

- View A: The implementation costs incurred by each partner should be capitalized to each partner’s one-tenth of the software asset that it proportionally consolidates.

- View B: The implementation costs incurred by each partner should be expensed by the individual partner.

Most Group members supported for View A and shared the following:

- Unlike the prior submission, the government partnership owns and controls the underlying cloud computing arrangement (which is an asset of the government partnership) for which implementation activities occur at the individual partner level to enable each partner to use the asset. So, a partner’s proportionate consolidation of its share of the partnership would allow capitalization of the implementation costs to occur. The asset to which the implementation costs would relate would be the partner’s one-tenth interest in the underlying cloud computing arrangement.

- Some Group members noted that if the implementation costs are essential to operating the software and to each partner benefiting from their interest in the partnership, then the costs should be capitalized.

- Section PS 3150 would allow the partnership to recognize the cloud computing arrangement as a software asset. As a result, each partner is effectively recognizing one-tenth of the software asset as part of its interest in the partnership.

- While structure should not be the deciding factor, two Group members felt that having the partnership incur all the implementation costs might be the most straightforward scenario.

Other members also shared the following perspectives:

- A few Group members supported View B. One Group member noted that, notwithstanding the changes in the fact pattern to the previous submission, the same concepts should remain applicable and implementation costs should be expensed.

- A Group member gave an example of an asset such as a fishing boat: Would it only hold value if a fishing license were granted? They noted that the inherent cost of cloud computing arrangements, similar to the fishing boat, ought to remain with the software rather than the asset itself. However, the Group member recognized that control over the software must be established.

The Group concluded that PSAB should consider providing additional guidance and clarity for how partners in a government partnership are to account for implementation costs they incur related to a cloud computing arrangement that is a service. Although most Group members supported View A, the Group encouraged PSAB to address the concerns discussed.

Back to top